Luigi and me, part two

Los Angeles, 2019

Continued from Friday.

Early on the morning of the protest, we assemble in secret at Starbucks.

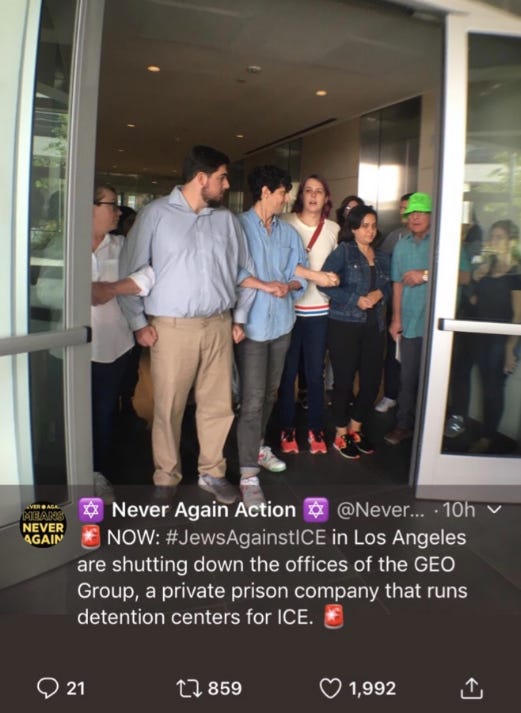

I’ve called in sick at work in order to volunteer with Never Again Action: Jewish activists against genocide.

(Though it feels like a cosmic error, I am not Jewish. Allies are, apparently, welcome.)

Our target is GEO Group, an operator of private prisons. They’ve drawn our ire by running ICE detention facilities: they are (profitably) executing Trump’s anti-immigration policies.

The GEO Group office is near LAX. I live in Los Feliz. In normal circumstances, one doesn’t drive to the airport from the east side of Los Angeles for anything short of the second coming, and then only if there’s free parking.

(If I were a comedian, I would have fun with Jesus: famously Jewish, and not the last to have mixed feelings about it. I think of Christ’s fellow Jews, only twelve of whom were moved to convert—what about the rest?

— Did you hear about the Nazarene? Turned water into wine!

— Sure. But did you taste it?)

Leaving Starbucks, my spirits are high. I am nervous, but adrenaline is doing its thrilling work.

I am rather more high-strung than your average bear. But today my companions—my fellow protestors—look distinctly more nervous than I feel. This is unusual.

As planned, we assemble slowly in the office building’s lobby, entering one by one or in pairs. We do our best to seem law-abiding—almost in love with the law.

The lobby is sleek; the windows are enormous. If shit goes down, it will be well-lit.

It’s time. We link arms at the elbow in front of the only elevator bank, forming a human wall.

The security guard, who was slow to notice us, asks what we’re doing. He is a man Of Color. I feel a flicker of moral ambivalence.

The guard asks again what we’re doing. He looks tired already.

A protestor explains that we are here against the GEO Group and ICE. The guard says that he understands. He even supports us. But again he must ask us to stop.

We decline. He calls the police.

So far, so good.

Officeworkers arrive. They are confused. The security guard explains that police are on their way. Most of the officeworkers cut their losses and walk away. Some linger outside, making calls. Some photograph us.

Eventually an officeworker decides he’s had enough. He tells us that he supports our cause. He tells us that he does not work for GEO Group. I realize that I have no idea how many companies have offices here—that he could easily be telling the truth.

But we remember our training. We are firm in our resolve. I say, “This is what we’ve decided to do.”

He seems to think that we are, in some way, kidding.

The officeworker tries to force his way through our wall of elbows and shoulders. Honorably, he chooses a pair of men to seek to breach. I am one of them. He fails.

When we rebuff him, he appears shocked. Finally, he walks away.

It is one of the most thrilling moments of my life.

Playing Red Rover as a kid did not prepare me for doing my job. But it did prepare me to stop this man from doing his.

This sequence—flatter, cajole, attempt to breach—is repeated by several more officeworkers over the course of the next hour. All fail. This includes at least one woman, who implements Sheryl Sandberg’s advice as literally as possible.

If nothing else, we have succeed in being a pain in the ass. A current of excitement runs through our line.

We are impregnable.

At which point the police arrive. Several of them.

The cop in charge is older than the others; his vibe is Baseball Dad.

He approaches me first. This I was not expecting.

You know you’re dealing with a ragtag/motley crew when I appear most likely to be reasonable. (Less flatteringly, I could’ve appeared most likely to fold under pressure.)

At our training a week ago, a volunteer lawyer explained that Los Angeles County is a decent place to get arrested. No guarantees, but we could reasonably—as peaceful protestors—expect mild treatment from police and prosecutors.

I am trying to keep this in mind as the cop, standing quite close, explains the severity of resisting arrest. Panicked thought: What if the lawyer was wrong? What if the lawyer wasn’t a lawyer, just someone’s unmedicated roommate?

The cop says that we’ve made our point. That it’ll be better for everyone if we start letting folks through.

Adrenaline, by this point, has replaced most of my blood. It steadies me and deepens my conviction: I can’t let the others down. I can’t be the one to break the line.

I watch myself say to the cop, “This is what we’ve decided to do.”

The next part happens quickly. He places a hand on my shoulder, gently but firmly turning me around. Handcuffs.

His speech about resisting arrest, I realize, was only more cajoling. Presumably, a protest ended by persuasion (or by feigned threats) means less paperwork than a protest ended by making arrests.

But we did not falter.

We are arrested.

We did it.

After the leader-cop reads me my rights—exactly like on Law & Order—he says something like, “Well done.” I’m beaming. I’m—a pleasure to have in class? Stockholm Syndrome doesn’t take long.

We are put into vans and driven to jail, where we are handcuffed to a metal bench.

At our training we were told that, while detained, we should speak as little as possible—banalities or silence. After all, anything you say can be used against you in a court of law.

But some of our number are naturally chatty. Others are urging them not to be. Tensions are rising.

One hour turns into two. The people handcuffed to this bench are beginning to strike me as crazy. Which is a bad sign, because I’m one of them.

My adrenaline is gone. Actually, more than that is gone.

I feel like the dog I grew up with, TJ—or, Turbo Joe. He’d sprint insanely around the house, around the yard, in circles, finally collapsing in happy exhaustion.

My anger is exhausted. I’m coming back to myself.

And I cannot avoid the feeling—awkward under the circumstances—that I dislike being handcuffed to a bench. Quite a lot, in fact. But it does give one time to think.

I’d never entirely made up my mind about whether ICE was committing genocide.

How, I wonder, do other countries approach these matters?

It was there, on that bench, in that moment, that the truth fell on my head.

The truth is that I know nothing about immigration policy.