We have lived too much in the minds of others, have too much unguaranteed capital on deposit there. — Ashbery

Does the bodyguard know which sections of the National Bank’s yearly report on debt service have been falsified? — Barthelme

Nelson Mandela said, “It always seems impossible until it’s done.” He presumably had constructive goals in mind, but the sentiment also applies to crime.

If you’ll grant that we’re overdue for a great heist movie, the question is: what should they steal?

I have three ideas.

The Town 2: This “Town” Ain’t Town Enough (for the Town of Us)

In 1990, two men dressed as cops walked into Boston’s Gardner Museum and announced they were robbing it. They made off with thirteen masterpieces, including Rembrandt’s only seascape. None have been recovered; the robbery remains unsolved. To this day, thirteen empty frames hang in the Gardner’s galleries—as if waiting for the paintings to come home.

One of the primary suspects in the robbery went on to scam his way into becoming a Hollywood screenwriter, later dying in Colombia under arguably suspicious circumstances—meaning that his biopic could be pitched as Adaptation meets Heat meets Confessions of a Dangerous Mind.

It really happened, all of it! The only mystery greater than the robbery itself is the fact that the greatest theft of private property in American history hasn’t been made into a movie. (As opposed to an otherwise admirable-seeming Netflix docuseries, from whose trailer I robbed that line about waiting for the paintings to come home.)

Golden parachute

In the 1970s, the difficulty level of hijacking an airplane fell somewhere between long division and building a futon from IKEA. Mass commercial air travel was in full swing—with a security regime that looks positively freewheeling in post-9/11 hindsight. Call it hijackapalooza. Don’t call it that? Fine, don’t call it that. Narc.

In this way, a man known only as D.B. Cooper hijacked a flight to Seattle, compelling the pilots to land just long enough for $200,000—over $1.3 million in today’s dollars—to be delivered onboard by the authorities.

Once the plane took off again and reached cruising altitude over the Pacific Northwest, Cooper took the cash, put on a parachute, opened an emergency exit and jumped out, never to be seen again.

Either Paul Greengrass makes this into a movie, or I start hijacking airplanes crying.

Equities unbound

“Mahwah” is not only the sound I make when I’m crying; it’s also a town in northern New Jersey.

Mahwah is additionally—improbably enough—the true home of the New York Stock Exchange (NYSE). While fleshbound stockbrokers continue to Buy and Sell by gesturing at each other in downtown Manhattan, their exertions largely benefit photographers and tourists, like colonial Williamsburg. The world’s largest financial market’s actual machinery—hyper-specialized computers known as matching engines—are located in NYSE’s Mahwah data center.

It follows, then, that the operation, maintenance, and repair of this machinery also take place there. Surely this makes Mahwah the perfect setting for a heist in the style of Mission Impossible or National Treasure; while Manhattan, since 9/11, has been crawling with machine-gun toting cops from the Battery to 57th street—amidst, presumably, an alphabet soup of skulking feds in hardly smaller numbers—suburban New Jersey remains criminally inviting by comparison.

But if we’re making a heist movie about the stock market, what is it that we’re stealing? If, as in Zoolander, “It’s in the computer,” what is it that “it”… is?

One word for you, son. Just one word, and it’s not “plastics.”

Information!!

The sun is setting on big tobacco; for big oil, it’s well past noon. Not so for big data.

People make money in the stock market by knowing things no one else knows. Sometimes this is done illegally, as with leaked tips on the results of clinical trials for new drugs; someone is guilty of insider trading when they’ve bought or sold stock based on “material non-public information.” For our purposes, the point is this: when a company is public, its secrets are lucrative.1

What draws our ragtag team of ambitious criminals to Mahwah, then, is simple. If one company’s secrets are valuably marketable, how valuable are the secrets of the market itself?

Short of lending money at interest or selling drugs (or financing mergers & acquisitions during a downswing in antitrust enforcement), there’s no more guaranteed route to indecent wealth than knowledge of the near future of the stock market.

In 2013, someone hacked the Twitter account of the Associated Press newswire and tweeted that the White House had been bombed. The stock market plunged. The tweet was quickly deleted and revealed as fake—but by the time the market recovered, the person behind the hack would have already profited handsomely in the futures market—having placed, prior to the tweet, an impossibly prescient bet: the sudden downturn that no one saw coming.

Let’s imagine our Mahwah criminals are amateurs. Like anyone else, they start by Googling.

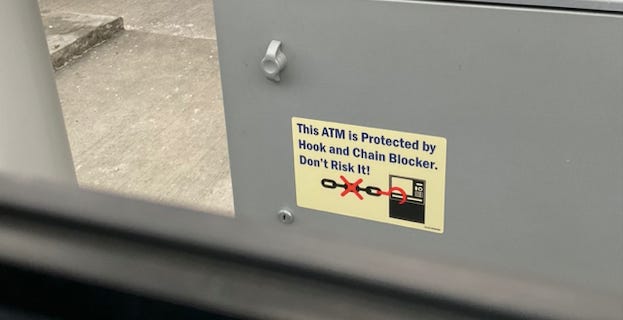

While the NYSE’s website says that the stock market’s critical technologies—which is to say, the components of the matching engines, along with their network connections to banks, hedge funds, etc.—“are not disclosed and subject to change,” literally anyone could probably observe which networking vendor the NYSE favors by spending a week or two working from a Mahwah Starbucks.

And I do mean anyone. Like, look at the drive-thru line at Starbucks in Mahwah. Are there lots of Cisco trucks, or more Juniper trucks? Bam. That’s material non-public information, baby. Or it would be, except that in this case it was obtained legally. (Whether the laws of man accord with those of God when it comes to venti Frappuccinos I will leave to the Archdiocese of Bergen County.)

Let’s say we’ve determined that the NYSE uses Cisco equipment for its fiberoptic switches. Helpfully, this enables our cinematic criminals to both optimize their own gear and to build their Spotify heist playlist around “The Thong Song,” by Sisqo, whose name is homophonic with Cisco, the manufacturer of networking equipment mentioned earlier in this quicksand-ass paragraph.

…Now when do we start the actual crime?

Mahwah’s matching engines receive, aggregate, and execute Buy and Sell orders from stock traders, both human and algorithmic, thousands of times per second. A criminal (or enterprising less-scrupulous day trader2 (in a movie)) could get a job as a utility lineman in North Jersey long enough to form an educated guess about which underground cable carries fiberoptic signal to the NYSE data center.

By installing an optical splitter on this cable and monitoring its volume of passthrough data—i.e., how much “water” is in the “pipe”—you wouldn’t learn anything about (almost certainly encrypted) individual trades, but you might learn a great deal about overall trading velocity in real time—or rather, fractions of a second before real time, as finding the right cable could mean anticipating the flow of buy/sell orders on their way to execution in the matching engines.

And that’s material non-public information (baby).

Apropos of nothing, my Venmo is @TheBeatlesWereAGoodBand.

Just kidding about my Venmo, but I’m serious about the Beatles, and I’m also serious about my Venmo.

Assume for a second that any of this makes sense. How lucrative could such a caper really be?

To answer that, ask yourself why Robinhood, the stock trading app for the unwashed masses, is free to use—i.e., why the name of their company is hideously ironic.

Robinhood sells what’s called “order flow” to hedge funds. When Joe Sixpack buys stock, his order doesn’t go straight to the matching engine; the privilege of unmediated access to the market is reserved for institutions who can afford to “co-locate” their servers at the data center in Mahwah.

This means that a hedge fund buying Robinhood’s order flow learns what hundreds of thousands of day traders are doing—before they’re permitted to do it. In this way, the hedge fund gains knowledge of the near future of the stock market. That’s money in the bank (which the banks they invest in will sell you (with interest))—and it’s legal. Would you like whipped cream with that?

Meanwhile, my idea of tapping into fiber cables around Mahwah might not actually work for several dozen reasons, and either way I can only assume it would be wildly illegal. In my head, though, it’s kinda like when Reddit got its hands on Gamestop stock—trying to beat the fat cats at their own game has a certain charm. The key to any team of on-screen criminals is their ragtag nature. Moxie, also.

Anyway, I imagine the steps outlined above as components of a montage early in the movie; not until a member of the team is hired as a night janitor at the data center do we really get to go bananas: thumb drives, rappelling down from ceilings so as to avoid the pressure sensors on the floor, Stuxnet-level maneuvers… solving equations on blackboards whose authors had assumed them to be unsolvable… and when the janitor finally takes off his glasses, then, and only then, does the colleague he’s crushing on realize how beautiful he’s been all along.

If it sounds impossible, it’s only because it hasn’t been done yet.

See you Friday, dear friends.

Public companies are those traded on the stock market. That includes most companies you’ve heard of and plenty you haven’t, though there are a couple behemoths—Koch Industries and Cargill are the biggest—which have chosen, for not necessarily nefarious reasons, to remain private.

aka amateur investor